Contents

Inquiries

Celestial Defense of Atlanta Georgia has over 30 years experience assisting contractors, their counsel, and even the government itself on a few occasions, with ingenious solutions to difficult government contract compliance problems and disputed issues, including ancillary disciplines like purchasing, accounting, estimating and manufacturing.

To discuss the requirements for a particular contractor business system review and the steps you need to take to pass them or how to respond to an unfavorable system review report contact us to speak with one of our experts or call 770-777-2090

Contractor Business System Reviews

by: Gregory L. Fordham

Contractor business systems, which include a contractor's accounting, estimating, and purchasing systems, along with three others, produce critical data that contracting officers use to help negotiate and manage defense contracts. These systems and their related internal controls act as important safeguards against fraud, waste, and abuse of federal funding. As a result, the federal and defense acquisition regulations impose standards for how contractor business systems should operate and then require require the review of these systems when review thresholds are reached. These system reviews are the Contractor Puchasing System Review (CPSR), Material Management and Accounting (MMAS) System Review, Earned Value Management (EVM) System Review, Estimating System Review, Accounting System Review, and the Property Management Review.

The Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA), through Administrative Contracting Officers (ACO), generally has responsibility for deciding whether contractor business systems are acceptable and then either approving or rejecting as unacceptable contractors’ business systems. The reviews and audits themselves, on which ACO decisions are based, are conducted, depending on the businsess system being reviewed, by Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA) reveiw teams or auditors from the Defense Contract Audit Agency (DCAA).

The following sections examine the six contractor business system reviews and explains the general purpose for these reviews, the thresholds triggering when contractors will be subjected to them, how they are administered and conducted, the nature of a significant deficiency, and how contractors can improve their chances at passing them, minimizing an adverse effect, and how to respond to adverse reports.

The following table lists the six contractor business systems and then identifies the cognizant agency overseeing them, the regulations governing those systems, and the system pass rate for each review. Naturally, the failure rate is the inverse of the stated system pass rates. Thus, pass rate of 99 percent means that only about 1 percent of contractor systems fail the review and are deemed unacceptable.

| BUSINESS SYSTEM REVIEW | COGNIZANT AGENCY |

GOVERNING REGULATIONS & TRIGGERING THRESHOLDS | PASS RATE |

| Accounting System | DCAA |

DFARS 42.75 & 52.242-7006 - Under DFARS 42.7502 accounting system reviews are required for contractors receiving cost-reimbursement, incentive type, time-and-materials, or labor-hour contracts, or contracts which provide for progress payments based on costs or on a percentage or stage of completion. Contract size or size of the contractor or its entity status are not considerations for determining whether or not this kind of review is warranted. Rather, the need for a contractor to receive a cost reimbursement, incentive type, time-and-materials, or labor-hour contract or contracts which provide for progress payments based on costs or on a percentage or stage of completion is what triggers the need for an accounting system review. There is no stated frequency for how often a contractor's accounting system can be subjected to review once it has been determined to be acceptable. While conceivably a review could be performed annually, it is unlikely that it would happen unless deficiencies were subsequently discovered during other reviews of the contractor's operations or during the required surveillance of the contractor's accounting system required under 3.2 of the DCMA Manual for Contractor Business Systems. There is no flow down requirement of this clause by prime contractors. In the event that the prime or upper tier contractor awards a subcontract to a subcontractor that otherwise would be covered by the accounting system requirement the responsibility for the subcontractor to have a proper accounting system remains with the prime contractor and it would be their responsibility to ensure that the subcontractor has an adequate accounting system, although whatever requirements the prime or upper tier subcontractor had could be different from the requirements of this requirement. |

99 % |

| Estimating System | DCAA |

DFARS 15.407-5 & 52.215-7002 - Under DFARS 15.407-5-70(b)(2) an estimating system system disclosure, maintenance, and review applies to large business contractors receiving in the preceding physical year $50 million or more in contract awards at any tier for which cost or pricing data were required, although it can also apply to large business contractors performing $10 million or more if the contracting officer with ACO concurrence think it is in the best interest of the government. There is no stated frequency for how often a contractor's estimating system can be subjected to the disclosure, maintenance, and review requirement once it has been determined to be acceptable. While conceivably a review could be performed annually, it is unlikely that it would happen that frequently. Most likely it would not happen again for 3 to 5 years, although the frequency is risk based. Since DoD policy is that all contractors should have estimating systems that produce well supported proposals, according to the DCMA Business System Review manual, it is also possible for the ACO to waive the disclosure, maintenance and review requirement for estimating systems of other than large business contracts and still evaluate a contractor's estimating system if deficiencies have been found to exist with other proposals where cost or pricing data have been required or where deficiencies have been reported in other business system reviews. There is no stated frequency for how often a contractor's estimating system can be subjected to review once it has been determined to be acceptable. While conceivably a review could be performed annually, it is unlikely that it would happen unless deficiencies were subsequently discovered during other reviews of the contractor's operations or during the required surveillance of the contractor's estimating system required under 4.2 of the DCMA Manual for Contractor Business Systems. There is no flowdow requirement of this clause. While the trigger for being subject to an estimating system review is based on awards at any tier, in order for the government to have the ability to pursue an estimating system review a contractor would have to have at least one prime contract. Otherwise, the government would not have privity of contract with the contractor and would have no basis for conducting the estimating system review. Once triggered, however, the government would have wide ranging review of a contractor's estimating system processes. |

22 % |

| Material Management and Accounting (MMAS) |

DCAA |

DFARS 42.72 & 52.242-7004 - The criteria for MMAS reviews are a two tiered where the first tier determines the triggering threshold and the second tier determines the contracts applicable to the MMAS system criteria. For the tier 1 triggering condition, under DFARS 42.7200(b)(2) and 42.7203(a) and (b) material management and accounting system reviews may be conducted in two situations. The first is when contractors have $40 million or more of qualified sales to the government in its preceding fiscal year. Qualified sales are those awards 1) subject to the submission of cost or pricing data or 2) priced on a basis other than firm fixed price or fixed priced with economic price adjustment. Qualifying sales include contracts, subcontracts, and contract modification. The second condition when a MMAS review can be required is when the ACO, with advice from the auditor, determines that a MMAS review is warranted based on a risk assessment of the contractor's prior performance. In this case there is no dollar threshold that the contractor must hit prior to the unilateral determination by the ACO. If the contractor is only acting as a subcontractor and does not have at least 1 contract under ACO oversight then there would be no basis for the government to conduct the MMAS review. The Tier 1 review requirement does not apply to small businesses, educational institutions, or nonprofit organizations. For the tier 2 applicability criteria the MMAS system review applies only to contracts exceeding the simplified acquisition threshold that are not for the acquisition of commercial items and are either— There is no stated frequency for how often a contractor's MMAS can be subjected to review once it has been determined to be acceptable. While conceivably a review could be performed annually, it is unlikely that it would happen unless deficiencies were subsequently discovered during other reviews of the contractor's operations or during the required surveillance of the contractor's MMAS required under 6.2 of the DCMA Manual for Contractor Business Systems. There is no flow-down requirement of this clause. Since subcontracts are included in the Tier 1 triggering condition, they are not excluded from consideration as a triggering condition but without these clauses in the subcontract the government will not have any basis for conducting a MMAS review without the contractor having at least 1 prime contract containing this clause or some other prime contracts being overseen by the ACO where the ACO can unilaterally determine, with advice from the auditor, that a MMAS review is warranted based on a risk assessment of contractor's past performance. |

25 % |

| Purchasing (CPSR) | DCMA |

FAR 44.3, DFARS 44.3 & 52.244-7001 - Under FAR 44.302(a) a determination is made whether to have a Contractor Purchasing System Review (CPSR) whenever a contractor is expected to receive $25 million or more in negotiated prime contracts in the next year. Under DFARS 44.302(a) the threshold has been raised to $50 million for defense prime contracts. Essentially, competitively awarded contracts and commercial item contracts are excluded from the dollar threshold calculation. Under FAR 44.302(b) after the initial determination is made that a Contractor Purchasing System Review (CPSR) is warranted the ACO shall make another determination at least every 3 years whether another review is necessary. Since award levels can rise and fall quite dramatically in these days of the government's bundling practices it is quite possible that a contractor meeting the trigger threshold could be limited to only certain years and not something that is a recurring condition. There is no flow-down requirement for this clause and since the triggering condition is clearly negotiated prime contracts a contractor that performs mostly as a subcontractor could easily avoid meeting the trigger threshold. Once met, however, the contractor's purchasing practices and source selection methods would be subject to review. |

21 % |

| Property Management | DCMA |

FAR 45.105 & 52.245-1, DFARS 45.105 & 52.245-7003 - A contractor is required to have and maintain an acceptable property management system whenever government property will be furnished or acquired under the contract. Contract size or size of the contractor or its entity status are not considerations to the applicability of this requirement. There is no stated frequency for how often a contractor's property management system can be subjected to review once it has been determined to be acceptable. It can be as often as needed. FAR 45.105(a) permits agencies to conduct the analysis, "as frequently as conditions warrant, in accordance with agency procedures". While there is no flow-down requirement for either the FAR or DFAR property contract clauses, there is a requirement in paragraph (f)(1)(v) of the FAR 52.245-1 property clause for the contractor to ensure appropriate flow down of contract terms and conditions as well as periodically perform property reviews to determine the adequacy of subcontractor property management systems. |

99 % |

| Earned Value Management (EVM) | DCMA |

DFARS 34.2 & 52.234-7002 - An approved Earned Value Management system is required for cost and incentive defense contracts of $100 million or more. An approved Earned Value Management system can also be required for cost or incentive defense contracts less than $100 million but over $20 million when requested by government stakeholders such as PCOs, program managers, or other government organizations. Size of the contractor or its entity status are not considerations for whether or not this kind of review is warranted. There is no stated frequency for how often a contractor's Earned Value Management can be subjected to review once it has been determined to be acceptable. It likely would not happen unless deficiencies were subsequently discovered during other reviews of the contractor's operations or during the required surveillance of the contractor's EVM system required under 5.2 of the DCMA Manual for Contractor Business Systems. Paragraph (k) of DFARS 52.234-7002 requires prime contractors to impose these requirements on selected subcontractors or on those performing certain efforts planned for subcontractors. |

99 % |

As is apparent from the above table, most of the contractor system reviews are governed by only the DFARS. Thus, there is no comparable requirement under the FAR for many of these business system reviews. The two exceptions are the contractor purchasing system (CPSR) and the property management system. The contractor purchasing system is covered by both FAR and DFAR regulations, although the DFAR is much more specific. With regard to property management, the FAR recognizes contractor reviews but it is only the DFAR that provides for detailed review requirements.

There are numerous differences between the above cited regulations that will appear in a contractor's contract and the DCMA manual on Contractor Business System Reviews. Some of those differences are the result of deviations that have been obtained by DoD from the FAR regulations. In many cases those deviations increase thresholds so that the reviews will be subject to fewer instances and targeted more to the situations that likely matter, particularly in a time where thresholds for all kinds of things have been dramatically increased over the years from the initial starting points.

Another difference in the DCMA manual is that there are often more detailed instructions to government personnel about how to manage the review process, obtain approvals, and communicate with contractors. These differences can be significant when a contractor is trying to understand the process, manage expectations, and deal effectively with any issues. Consequently, there is considerable reason for contractors to be intimately familiar with both the contract requirements as well as these more detailed instructions and know whether the more detailed instructions are grounded in actual contract requirements and not just based on non-binding agency instruction.

Another interesting metric in the above table is that while accounting, property and earned value management systems tend to have high pass rates the other three systems of estimating, material management and purchasing (CPSR) tend to have very low pass rates as a result of significant deficiencies having been found.

The DFARS is the only Agency FAR Supplement involving any of these contractor business systems. Thus, contractors are not likely to encounter business system reviews unless they are performing Defense contracts and meet or exceed the thresholds for needing a business system review.

There have been a number of other administrative factors that have effected the likelihood that contractors will experience a business system review. Historically the Defense Contract Audit Agency (DCAA) was primarily responsible for conducting contractor business system reviews of accounting, estimating and material management. The Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA) was principally responsible for property management system reviews. Both agencies performed different parts of purchasing and earned value management reviews. The split responsibility often meant that the two agencies would provide different opinions about the acceptability of those systems, at least for the portions that they covered, which was often quite confusing. As a result, around 2012 the responsibility for the determining acceptable business systems was re-allocated such that DCAA would do only accounting, estimating, and material management system reviews and DCMA would do only purchasing, property management and earned value management system reviews.

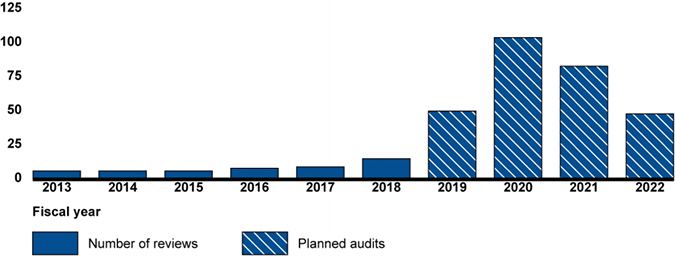

DCMA does about 110 purchasing system reviews each year along with about 1,000 property management reviews, and 300 Earned Value Management reviews. By contrast, DCAA was only doing about 8 accounting, estimating, or material management reviews each year. Essentially, DCAA had been experiencing declining manpower and growing backlogs of incurred cost audits. As a result, contractor business system reviews took a back seat through about 2017.

Congressional mandates in the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) of 2017 forced DCAA to refocus its energies and realign priorities. As a result, DCAA was targeting more like 80 to 100 business system reviews per year through 2022. As a result of the pandemic, however, DCAA's big year of 2020 was likely pushed out. The effect of the pandemic on just how many system reviews DCAA will do for 2021 and 2022 is likely still uncertain. .

Thresholds

Contractor Business System Reviews can be large undertakings for both contractors and the government reviewers. Considering the diversity of the various business systems, each one has its own thresholds for determining when a review of the contractor's system is warranted. While all contractors likely have these various systems, not all contractors are required to have their systems reviewed. Indeed, the criteria for determining when a contractor should have a review are set at rather high levels. As a result, it tends to be only large contractors that are required to have a system review. In fact, in some cases, small businesses are exempt from the review requirement even if they meet other threshold requirements.

For the most part, the various system reviews apply to contractors performing contracts that are somehow related to costs. The relationship may only be at the proposal stage where contracts are cost justified determination might only apply. The property management system is the only one that is not affected by contract cost type issues. The following table provides the thresholds for each of the various contractor business system reviews.

SYSTEM |

REG CITATION |

THRESHOLD |

ACCOUNTING |

DFARS 42.7502 |

Contractors receiving cost-reimbursement, incentive type, time-and-materials, or labor-hour contracts, or contracts which provide for progress payments based on costs or on a percentage or stage of completion, shall maintain an accounting system but no stated trigger or frequency for system review. |

ESTIMATING |

DFARS 15.407-5-70(b)(2) |

Large business contractor and in preceding fiscal year had $50 million or more in DoD prime or subcontract awards requiring Cost or Pricing Data or $10 million or more requiring cost or pricing data and Contracting Officer with concurrence or request of ACO thinks it is in best interest of Govt, which generally means that estimating system problems are believed to exist or its sales are predominately government sales. There is no stated frequency for the review. While conceivably a review could be performed annually, it is unlikely that it would happen that frequently. Most likely it would not happen again for 3 to 5 years, although the frequency is risk based. |

MATERIAL MANAGEMENT (MMAS) |

DFARS 42.7200(b)(2) and 42.7203(a) and (b) |

Large business contractor and in preceding fiscal year had $40 million or more in prime or subcontract awards (including modifications) of "qualifying sales" and the ACO with advice from the auditor determines that a MMAS review is needed based on a risk assessment of contractor’s past performance and current vulnerability. Qualifying sales covers a variety of different contract awards such as contracts other than firm fixed priced contracts or fixed price with economic price adjustment (essentially flexibly priced contracts that can be cost based) as well as any contracts where Cost or Pricing data were required. Just like for the Estimating System Review there is no stated frequency for how often a Material Management System review would occur. Also, like with the Estimating System it could be required as often as annually assuming the trigger conditions existed, however, this review does also require both ACO and advice from the auditor that a review is warranted. Clearly, the frequency of the Material Management System review is risk based. |

PURCHASING (CPSR) |

FAR 44.302(a), DFARS 44.302(a) |

Under FAR 44.302(a), the ACO shall determine whether a purchasing system review is necessary based on past performance of the contractor, and the volume, complexity and dollar value of the contractor’s subcontracts when the contractor’s prime contract, subcontract and contract modifications on government contracts are expected to exceed $25 million in the next 12 months. Under DFAR 44.302(a), sales to the Government are expected to exceed $50 million in next 12 months. Once an initial determination is made the ACO shall make a determination whether subsequent reviews are needed at least every 3 years and then conduct a review if necessary. |

PROPERTY MNGT |

DFARS 45.105 |

Whenever contractor has government property but no stated trigger or frequency for system review. Essentially as required or when deemed necessary by ACO as a result of deficiency indicators appearing. |

EARNED VALUE (EVM) |

DFARS 34.201(1)(ii) |

For cost or incentive contracts and subcontracts valued at $50,000,000 or more |

Prior to the "Peace Economy" contractor business system reviews were fairly common, of course the thresholds were much smaller, too. The thresholds have increased over time and are now, for at least most Contractor Business System reviews, quite high at typically between $25 to $50 million in annual contract awards, including subcontract awards. Naturally, these high dollar amounts have limited the applicability of these reviews to mostly large contractors.

In addition, thresholds of other contracting methods have increased as well. For example, the threshold for Cost or Pricing Data has risen from $100,000 to $2 million in the last 30 years as has the threshold for Cost Accounting Standards. Since the annual dollar amount of contract awards is often based on contracts with these other conditions, that has also worked to reduce the number of contractors that could be subject to the these system reviews. While government agencies like DCMA may have insight into government prime contract awards they tend to lack visibility into subcontract awards and then into the other specifics like whether the Cost Accounting Standards were applicable or whether Cost or Pricing Data were required. Even contractors often lack easy identification of which of their contracts and subcontracts actually are subject to Cost Accounting Standards. The mere existence of the clause in the contract is not predictive, since it can be self eliminating.

Over the last 30 years contracting methods have also changed. For example, commercial Item contracting is much more common now than it was even 20 years ago. Since commercial item contracts tend to be exempt from these reviews, their more widespread use has also reduced the likelihood that contractors will encounter business system reviews.

Acceptable vs Unacceptable Systems and the Significance of "Significant Deficiencies"

When it comes to contractor business system reviews, whether the system is acceptable or unacceptable is a little different than what contractors normally encounter with other kinds of reviews and audits such as proposal audits or incurred costs audits. After all the focus of a system review is procedural and not transactional. In other words, it considers how does the system work and what does it produce as compared to the value of any particular proposal or contract.

While each of the system clauses tend to include various criteria that acceptable systems are expected to achieve, a transactional example of where the criteria was not met for a particular contract, is not necessarily the mark of an unacceptable system. In other words, the failure would need to be more systemic and apply to all the contracts being processed by the system.

In addition, an unacceptable system is one containing "significant deficiencies", As its very name implies, the issue is not just a deficiency or failure to achieve the acceptance criteria but a "significant deficiency". Thus, it seems quite possible for a contractor's system to have experienced failures to meet the various system criteria provided in the various contractor system clauses but those failures may still not rise to the level of a "significant deficiency".

In terms of a contractor business system, a “significant deficiency” means, ". . . [A] shortcoming in the system that materially affects the ability of officials of the Department of Defense to rely upon information produced by the system that is needed for management purposes." Based on this definition that appears in each of the various contractor business system clauses it seems obvious that a "significant deficiency" is more than a "one-off" or isolated occurrence. Rather, to be significant it must satisfy three different criteria of its own. First, it must effect the system. Second, it must have material effect. Third, it must effect the reliability of the information produced by the system for "management purposes".

Other than the above definition, which is the same one provided in each of the various business system clauses, there is no further explanation about what comprises a "significant deficiency". Rather, it is just a standard definition appearing in each of the various business system clauses as a kind of boilerplate. Thus, a significant deficiency is clearly going to be something determined on a case by case basis and very factually specific. To illustrate consider the following three situations.

Policies and Procedures for System Reviews.

The first situation involves policies and procedures. Each of the various business system clauses require contractors to have written policies and procedures describing their systems. Inevitably there can be differences in how the auditors versus the contractors think that the policies and procedures are expressed. Would preferences in how the policies and procedures should be described rise to the level of a "significant deficiency"?

If the system works as required regardless of how well it is described by the policies and procedures, one would think that differences in word smithing would not rise to the level of a "significant deficiency". In fact, even if there were system failures if they could not be traced and correlated to the written policies and procedures, the policies and procedures themselves would not seem to rise to a "significant deficiency". Clearly, on the other hand, if there were system deficiencies and those deficiencies made the system unreliable and the cause of those errors could be linked to errors in the policies and procedures that were being followed then that would seem to rise to the level of a "significant deficiency".

Vendor Quotes in Estimating System Reviews

In pricing situations the government is always pushing for the contractor to use the lowest obtained quote. There is never any requirement that the lowest obtained quote actually be used, however. There is not any such requirement in the criteria for estimating systems, either. Even with cost or pricing data there is no requirement that vendor quotes actually be used to develop the contractor's price. Rather, there is simply a requirement that vendor quotes be disclosed. If during a review of a contractor's estimating system it was determined that the contractor hardly ever used the lowest quote obtained would that rise to the level of a "significant deficiency"?

Again, the definition of "significant deficiency" means that the system data is materially unreliable for management purposes. Presumably under this definition, if, hypothetically speaking, the contractor always used the highest quote for estimating its costs but then always used the lowest quote when actually performing the contract that would seem to make the system data unreliable for predicting the contractor's actual costs. As a result, that would seem to meet the definition of a "significant deficiency".

On the other hand, if the contractor is estimating its costs and then actually performing the work using the vendor that provided the best value, a finding by the system review team that the estimate was not based on the lowest quote does not seem to meet the definition of a "significant deficiency". Instead, that situation would seem to verify that the contractor's estimating system is very reliable for estimating its costs.

With respect to the first situation above, where the contractor always used the highest quote for pricing but lowest quote for performance, perhaps there could be a basis for making a materiality argument to counter any "significant deficiency" finding if the difference was seemingly trivial but their is no explanation of the term materiality in the definition of "significant deficiency". Most likely attributes like predictability, consistency, and usefulness would outweigh the concept of materiality.

Actual Contract Terms for System Reviews

Where the concept of "significant deficiency" can really get skewed is with actual contract terms. In large respect the criteria for an acceptable system are configured around how DoD would like to see contractors operating for the benefit of DoD. That works well for prime contractors where the contract terms match the concepts of the system review and vice-versa. Even when the prime contract may have omitted certain essential clauses that can make very little difference. Prime contracts are often going to be interpreted as having all of the clauses it was required to have whether actually provided or not.

When the contractor that is subject to the review is a subcontractor, though, things can become much more complicated and less sensible. When the review involves post award performance based issues such as purchasing and material management, what interest or management purpose can DoD have when the subcontractor being examined has fixed priced contracts and no flexibly based financing arrangements? Furthermore, what interest or management purpose can DoD have when the subcontractor's prime customer is performing a fixed priced contract and the subcontract award was made after award of the prime? When the prime is performing a fixed priced contract does it even matter whether the subcontractor's contract with the prime is fixed priced or flexibly priced, at least for post award performance type reviews like material management and purchasing? What if the prime contractor has failed to pass down certain clauses or was not even required to flow-down certain clauses that would have made the system review more meaningful had the subcontractor been acting as a prime?

Granted, evaluation of a contractor's post award compliance with certain of the policy clauses like small business, buy American, and Defense Priorities and Allocations System (DPAS) could still be sensible even though the cost and pricing issues were negated by fixed price contract situations. The reality, however, is that business system reviews and the evaluation of a contractor's compliance with their criteria is not a cookie-cutter proposition. This is particularly true when trying to distinguish between excusable situations where the criteria were not followed because they may not have actually applied, verses occasional non-conforming exceptions that are not really systemic, verses "significant deficiencies" that are both non-conforming and systemic. The reality is that there are simply a lot of moving parts to these business system reviews and government auditors do not always get things right, particularly when they approach them in a mind-numbed, boilerplate, cookie-cutter fashion.

Informative Case Decisions Involving Contractor Business System Reviews

For the subject of contractor business system reviews there are not a lot of decisions from the Boards or Courts resolving the issue of "significant deficiency" but there are a couple of instructive decisions nonetheless. No less remarkable is that they turn in favor of the contractor because, as is often the case, the government reviewers simply did not know the regulatory requirements. Each of these cases are discussed below.

Raytheon Company

The first decision involves Raytheon Company, ASBCA Nos. 59435, 59436, 59437, 59438, 60056, 60057, 60058, 60059, 60060, 60061 (Feb 2021). In that case, the DCAA had found a "significant deficiency" during review of the company's estimating system and accounting systems.

With regard to the estimating systems review, DCAA issued a report finding a "significant deficiency" because DCAA claimed that the company should be using lowest available airfare when estimating the cost of its international travel and that it should not be including any provision for premium class airfare, as it was doing in accordance with its company travel policy. Raytheon argued that its policy was compliant with FAR 31.205-46(b) and properly considered the exception permitted under FAR 31.205-46(b). The estimating issue was resolved and DCAA approved the system when Raytheon adjusted its travel policy to include a more stringent approval process for business class travel and added a meaningful work upon arrival requirement.

With regard to the accounting system review, DCAA questioned any airfare with a seat class higher than coach and, once again, it did not consider any FAR 31.205-46(b) exceptions. To compute the amount of unallowable costs claimed by Raytheon, DCAA developed its own lowest available coach airfare as the lowest airfare allegedly available to Raytheon. The Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA) contracting officers issued final decisions (COFDs) asserting government claims and seeking repayment of the unallowable costs included in Raytheon's final indirect cost proposals for years 2007 and 2008 plus penalties. Raytheon appealed those decisions.

Since the estimating system issue had been resolved, all that was before the board were the accounting issues. The Board found in favor of Raytheon because the government failed to prove its case. Essentially, despite all of the government's complaints about travel premiums that had been claimed by Raytheon the cost principle at FAR 31.205-46(b) established a ceiling for the allowable costs. Consequently, there was no need for the Board to address the specifics about whether the premiums were allowable because the government never proved that Raytheon had actually claimed more costs than the ceiling allowed under the cost principle.

This was a systemic issue, since the issue being addressed was memorialized in Raytheon's travel policy and it was following that policy. The fact that Raytheon was following the policy meant that its consequences were reflected in its cost and pricing calculations for new work which would have an effect on data that DoD would use for management purposes and consequently the deficiency could rise to the level of a "significant deficiency".

The case also demonstrates how Raytheon was able to avoid having its estimating system disapproved without actually changing the outcome of how it would estimate costs. Rather, it was able to avoid the "significant deficiency" and having the system disallowed by implementing more stringent approval thresholds and adding the meaningful work upon arrival requirement. While both of these will impose non-value added cost to the travel process they would not have changed the estimating process in the same way that completing jettisoning recognition of premium travel in all situations even though the company would continue incurring the costs under its travel policy.

It is unfortunate that the basis for the government disallowance of the costs and disapproval of the accounting system was so badly flawed, although it is all too typical. Based on the decision it appears that there simply was no basis for the government's position. In that regard the case is also instructive about how badly all of government can perform. It is not unusual that DCAA had unfounded opinions in its reports. What is a little more amazing is that an ACO and DCMA could not be better informed and dissuaded from following DCAA over the cliff on this issue. This was not that complicated of an accounting issue. In addition, it is often possible to educate an ACO and even DCMA on the fallacies of a DCAA opinion and get a sensible decision from them. Of course, it often takes a lot of work by the contractor to do that. So, it is not just a matter of rebutting the DCAA opinion as many contractors do. Rather, it requires an education and documentation effort in order to persuade the ACO and DCMA about the actual requirement and why DCAA has so badly interpreted it.

A-T Solutions, Inc.

The second decision involves A-T Solutions, Inc. ASBCA 59338 (Feb 2017). In that case, A-T Solutions (ATS) was transferring training aids between divisions at catalog price instead of at cost. DCAA claimed that since A-T Solutions contract was a cost reimbursement contract that it was required to transfer the units at costs and not at price. Even though the cost principle at FAR 31.205-26 does not predicate the material transfer pricing methodology on contract type, DCAA took the position that the practice made ATS' accounting system unreliable as a result of a significant deficiency.

This was a systemic issue, since the issue of intercompany transfers at price was a company policy. The fact that A-T Solutions was following the policy meant that its consequences were reflected in its cost and pricing calculations for new work which would have an effect on data that DoD would use for management purposes and consequently the deficiency could rise to the level of a "significant deficiency". The offsetting reason for why it should not have been a "significant deficiency" warranting disallowance of the entire accounting system was that this situation was only an issue for this one cost reimbursement contract. The rest of the situations involved A-T Solutions fixed price contracts where this particular practice was not a problem.

To support its position with respect to the cost type contract the government offered numerous explanations for why ATS' treatment was problematic. In the end, the Board never found any of the government's arguments persuasive or having any basis in the regulations.

It is unfortunate that the basis for the government disallowance of the costs and disapproval of ATS' accounting system was so badly flawed, although it is all too typical. It is not unusual that DCAA had unfounded opinions in its reports. GAO has often found errors in DCAA reports ranging from 50 to 80 percent depending on the particular subject matter. What is a little more amazing is that the ACO and DCMA could not be better informed and dissuaded from following DCAA over the cliff on this issue. This issue was not that complicated of an accounting issue. In addition, it is often possible to educate an ACO and even DCMA on the fallacies of a DCAA opinion and get a sensible decision from them. It often takes a lot of work by the contractor to do that, however. So, it is not just a matter of rebutting the DCAA opinion as many contractors do. Rather, it requires an education and documentation effort in order to persuade the ACO and DCMA about the actual requirement and why DCAA has so badly interpreted it.

Summary of Significant Deficiency

Knowing and understanding significant deficiency is a key to Designing compliant business systems as well as conducting any assessment of a contractor's business system. It is not a cookie cutter process and boilerplate is not a good solution to the problem.. Even understanding what constitutes a "significant deficiency" is an important fist step to be being able to resolve system review findings effectively.

How Reviews are Conducted

Contractor business system reviews are complex processes and can take several weeks of field work where reviewers are on-site examining details of the contractor's system and supposedly collecting sufficient, competent, evidential matter necessary to support a final opinion. In addition, to the actual time required to perform the field work there can be initial assessment efforts where the contractor supplies various metric data so that the government can determine whether thresholds have been crossed and the contractor's business system warrants a review. Assuming a review is warranted, then prior to any field work, the contractor will likely be asked to provide lists and other data to the review panel so that they can begin to plan their review.

When the review begins it will be comprised of essentially three phases that contractor's frequently experience for other kinds of audits and reviews. Those three phases are the entrance conference, the actual field work, and the exit conference. All three can be quite important for successfully passing the review. So, it is not a matter of sitting back with fingers crossed and hoping for the best at the end. As stated previously, there are simply a lot of moving parts to these reviews. It is far too easy for the reviewers to come away with bad finding as was clearly evident in the two cases discussed above. Furthermore, once the bad finding is established it becomes a line in the sand for a lot of the regulator types where the review team is reluctant to admit a mistake and instead just tries harder to prove its bad position is actually justified as is evident in the A-T Solutions decision. Consequently, it is important for contractors to not only keep the lines of communications open but also be highly proficient in the "dance" that goes with these kinds of review. All to often the real issues are not about meeting the system criteria but overcoming the bogus finding. Thus, if one is simply focused on the cookie-cutter, criteria kind of approach, they are likely to just become the next failure statistic at some cost to their company. Each of the three phases is discussed in the sections that follow.

Entrance Conference

Typically, any kind of review that contractors experience will begin with an entrance conference. This is typically where the government introduces its team, explains the purpose of its review, identifies the data it wants to review, and establishes the protocols by which it wants to communicate with contractor personnel.

The business system review will be a little different than the other kinds of reviews that contractors experience such as pre-award audits of proposals and post award audits of contracts. Those kinds of reviews are typically focused on particular proposals or contracts. By contrast, the business system review is more systemic and company wide. As a result, this entrance conference can include a brief overview of the company that can include things like types of contracts, sizes of contracts, types of customers, etc. Considering all of the moving parts that can be part of these review this can be a good time for contractors to orient the review team to system parameters that they might not have noticed when reviewing other metrics and threshold data. A lack of flexibly priced contracts and financing payments as well as highly skewed performance as a prime and subcontractor can have significant effects on to what extent DoD needs to rely on the data for any kind of management function. In fact, in the right circumstances it is quite possible that however the contractor operates has no consequence on DoD at all such that its only effect is on how well the contractor atually performs its contracts and those kinds of things are not considered in these business system reviews that are more on the administrative side of things.

Actual Field Work

During the review the team will be reviewing the contractor's policies and procedures and examining various documents involving transactions selected in advance. Each day the lead analyst is to conduct daily briefings at the end of each day to keep communication open and to apprise the contractor about what the analysts are finding.

Things that can be fixed on the spot without further correction action necessary are essentially Contractor Action Requests (CAR) Level I. CAR Levels II through IV will be addressed after the field work is complete.

Exit Conference

After the review is complete the team should provide some kind of briefing to review the kinds of things that were found. This will not be a report, although it will likely be the kinds of things that will go into whatever report the team subsequently prepares and provides to the ACO.

Probably nothing provided to the contractor will be new. Most likely it will consist of the same things that the team has been revealing during the actual field work. The difference will be that the contractor can have had time to review materials from the earlier discussions and at least provide a more robust response and explanation. If the team appears to be on-track then the contractor maybe able to discuss, hypothetically at least, ideas for corrective actions or perhaps even advance reasons for why whatever the team thinks it has found is at least not a "significant deficiency". On the other hand, in the event that what the team reveals appears to be off-base, it is the time the contractor can support its assessment for why it believes the team has misconstrued the facts or the requirements.

In either case, hopefully the team will accurately convey whatever information the contractor provides. Contractors should not be surprised, however, if the team fails to convey whatever information the contractor provides or if it inaccurately and even falsely conveys whatever information the contractor provides. Contractors should also provide whatever information it provided to the team in writing with copies to relevant government managers, particularly if a disagreement appears to be developing.

Post Review

Once the review is completed the review team leader will issue a Level II CAR for any deficiencies still outstanding. The contractor will have 30 days to review, respond, and provide a Corrective Action Plan (CAP). Once received the review team leader will review the contractor's CAP for adequacy and advise the ACO in the final report.

Reports and Determinations

Essentially, a review team of either DCAA or DCMA will review the contractor's business system. As explained above, estimating, accounting, and material management systems are reviewed by DCAA and the others, like the CPSR, are reviewed by DCMA. At completion of the review, the review team will prepare a report and deliver it to the Administrative Contracting Officer (ACO). Whether a contractor system is compliant or not is a determination actually made by the ACO, although the review team will make recommendations. The auditors or review team may do the review, develop findings and make recommendations but the final decision is with the ACO. This is often a reality that contractors overlook. Auditors and analysts simply have no authority to bind the government. So, while it is always good practice for contractors to work with auditors and analysts, they do not make the decisions. This can be a positive thing for contractors because, unfortunately in many situations, auditors and analysts are motivated only to develop findings and can be reluctant to recognize the fallacy of whatever finding they have, even when those findings are contrary to law, regulations or contract terms as is clearly evidenced in the two cases previously reviewed.

If the ACO disagrees with the findings contained within the business system report after consultation with the functional specialist or auditor, the issue is subject to Board of Review (BoR) requirements. The ACO must notify the functional specialist or auditor in writing that he or she disagrees with findings in the business system report, provide the functional specialist or auditor with documented rationale for the disagreement, and request a BoR. Clearly, the administrative processes have been stacked to limit an ACO's ability to deviate from the review team's findings. It is important for contractors to understand the environmnent in which the ACO must work how best to respond to his findings and reports when they clearly contain errors.

Initial determination

If the ACO determines that no significant deficiencies exist within the business system, the ACO does not issue an initial determination, but proceeds with the issuance of a final determination which is discussed below. If there are significant deficiencies identified by the review team and the ACO agrees with those findings then the ACO is supposed to issue an initial determination within 10 days of receiving the report from the review team.

While the contract clauses tend to simply require the ACO to, "describe the deficiency in sufficient detail to allow the Contractor to understand the deficiency", the DCMA Contractor Business System Manual requires the initial determination to cite each significant deficiency in detail addressing the following items:

(a) Business System Criteria. Cite the business system clause, number, paragraph and the specific system criteria in its entirety.

(b) Deficiency. Describe the significant deficiency as it relates to the specific business system clause criteria and how the finding is not in compliance with the specific business system criteria.

(c) Impact. Describe the impact to the Government of the significant deficiency. The narrative must state how the significant deficiency materially affects the Government’s ability to rely on the information provided by the system.

It is worth noting that for any finding warranting an initial determination that the deficiencies must be "significant". Consequently, it is important that in the initial determination that the ACO not only identify some deficiency or some kind of error but that the error rise to the level of a "significant deficiency" and the justification of that error as a significant deficiency must be explained in the initial determination finding.

Contractor Response to Initial Determination.

The initial determination is supposed to request the contractor review each significant deficiency and provide a response to the initial determination within 30 calendar days. The initial determination is not supposed to include a request for the contractor so submit a Corrective Action Plan (CAP). That step is postponed until issuance of the Final Determination.

Since the contractor has 30 days to respond to the ACO's initial determination and since the initial determination is supposed to be so detailed, this is a great opportunity for the contractor to agree or rebut government's findings on two different levels. The first level is to agree or rebut whether the deficiencies actually exist as claimed. The second is to agree or rebut if whatever deficiencies were found rise to the level of a significant deficiency. After all, the contractor could agree with the problem findings and still explain that the findings do not rise to the level of a significant deficiency as explained previously.

When crafting their response the contractor does not simply want to rebut the finding but include considerable detail supporting its claim that the findings are not significant. Also, even though the initial determination does not include a request for a Corrective Action Plan, if the contractor is able to implement such a plan that would significantly or completely resolve the deficiencies that information should be included.

Within 30 calendar days of receipt of the contractor’s response to the initial determination, the ACO, in consultation with the functional specialist or auditor, evaluates the response provided by the contractor and issues a final determination. If the ACO cannot complete his evaluation of the contractor's response the ACO can request a 15 day extension. If the ACO cannot complete his evaluation within 45 days then the ACO can request another but final 15 day extension. So, 60 days is the maximum time that an ACO can have for evaluating the contractor's response to the initial determination.

Clearly, when deficiencies exist, there can be considerable time, at least 60 days and as much as 90 days, between the issuance of the ACO's initial report and the ACO's final determination. The contractor wants to use this time wisely to implement any corrections it thinks are necessary as well as prepare a detailed rebuttal that includes considerable, authoritative support for its rebuttal if it thinks the deficiencies are not significant, since the ACO will be sharing this information with others that will be reviewing his final decision. If there is a disagreement between the ACO and the functional specialist or auditor, that significant deficiencies no longer exist after reviewing the contractor’s response to the initial determination, the issue is subject to BoR requirements. The ACO must notify the functional specialist or auditor in writing that he or she disagrees that significant deficiencies no longer exist, provide the functional specialist or auditor with documented rationale for the disagreement, and request a BoR (not applicable to HNAO audits).

If the ACO determines, after consultation with the functional specialist or auditor, that all significant deficiencies have been corrected and no longer exist, the ACO prepares the final determination approving the business system. The appropriate CMO Contracts Director, Director for the regions and DCMAI of the CACO/DACO Group, or DCMAS Cost and Pricing Center Director, as defined in Section 2, “Responsibilities,” must review and concur with the ACO’s final determination approving the business system prior to issuance to the contractor.

If the ACO determines, after consultation with the functional specialist or auditor, that significant deficiencies still exist within the business system, the ACO prepares the final determination disapproving the business system.

Final Determination

As mentioned above in the section on initial determination, if there are no deficiencies identified by the review team and the ACO determines that no significant deficiencies exist within the business system, the ACO must issue the final determination within 10 calendar days of receipt of the business system report. The final determination will notify the contractor that the business system is approved.

Prior to issuing the final determination of an acceptable system where no deficiencies were found, the ACO must also obtain approvals from higher management. Specifically, the appropriate CMO Contracts Director for the regions and DCMAI, Director of the CACO/DACO Group, or DCMAS Cost and Pricing Center Director must review and concur with the ACO’s final determination approving the business system prior to issuance of the final determination to the contractor. Clearly, the 10 day issuance requirement when no deficiencies are found by the review team is very tight considering that the ACO must review the review team's findings and get concurrence from higher ups.

If there had been an initial determination of system deficiencies then after getting the contractors response the ACO must review that response with the review team and assess whether significant deficiencies still exist. If the ACO still thinks there are significant deficiencies he is to disapprove the system.

While the contract clauses tend not to provide much guidance about the nature of the final determination, the DCMA Contractor Business System Manual requires the ACO to provide a detailed justification of the disapproval that includes the following elements.

(1) Business System Criteria - Cite the business system clause, number, paragraph and the specific system criteria in its entirety.

(2) Deficiency - Describe the significant deficiency as it relates to the specific business system clause criteria and how the finding is not in compliance with the specific business system criteria.

(3) Impact - Describe the impact to the Government of the significant deficiency. The narrative must state how the significant deficiency materially affects the government’s ability to rely on the information provided by the system.

(4) Contractor’s Response - Provide a synopsis of the contractor’s response to the initial determination, if one was provided.

(5) ACO Analysis - Provide an independent analysis of the contractor’s response to include a discussion of any proposed or completed corrective action, and why, in the opinion of the ACO, the significant deficiency remains.

The final determination should also include a request that the contractor either correct the significant deficiencies or submit an acceptable CAP within 45 calendar days of receipt of the final determination as prescribed by DFARS 52.242-7005.

(1) The final determination must inform the contractor that an acceptable CAP will:

(a) Address the cause of each significant deficiency.

(b) Include actions to eliminate each significant deficiency.

(c) Include detailed milestones.

(d) Include target dates for full implementation of planned actions.

(2) A sample CAP must be attached to the final determination.

Finally, if the ACO determines that the CBS contains significant deficiencies, and withholds apply, the final determination must include a notice to withhold payments as prescribed by DFARS 52.242-7005 and include a list of the affected contracts for which withholding will apply.

Withheld Payments

If the ACO disapproves the contractor's business system and the contract contains the clause at DFARS 52.242.7005, the ACO is supposed to order withholding of payments as prescribed in DFARS 52.242.-7005. The clause permits withholding from progress payments and performance-based payments. In addition, it requires the ACO to direct the Contractor, in writing, to withhold five percent from its billings on interim cost vouchers on cost-reimbursement, labor-hour, and time-and-materials contracts. The withholding of payments only applies to contractor invoices submitted after the final determination disapproving the contractor's business system. Thus, it is not retroactive. Interestingly, there is no flow-down requirement of the DFARS 52.242-7005 clause. Consequently, the prospect for withholding appears limited to prime contractors and not to subcontractors with failed business systems. Of course, if the prime or upper tier subcontractor has passed down the DFARS 52.242-7005 clause then withholding could be possible. Clearly, the flow down of this clause is something that lower tier contractors should consider when doing their preaward contract reviews and be sure to object to its inclusion in contracts, since it is not a required flow down.

If it is just one contractor business system that is disapproved, the withholding amount is limited to 5 percent. If two or more systems have been disapproved the withholding amount is 10 percent. Although not stated, presumably the 10 percent amount would apply to contracts having both disapproved systems. For example, a contractor could have system deficiencies and disapproved systems for both property and accounting systems but not every contract would necessarily involve both property and accounting systems. In such a case, there is an argument to be made that only the 5 percent withholding would apply to contracts with just one deficient business system.

Withholding payments is intended to protect the government's interest when systems are potentially responsible for overcharging. Withholding of payments do not apply to payments on fixed price line items where performance is complete and the items have been accepted. Thus, as fixed priced line items are completed any prior withholding can be liquidated in a similar fashion to how progress payments themselves are liquidated.

Withholding of payments applies only to CAS covered contracts. This limitation is clearly established in paragraph (a) of DFARS 52.242-7005. In fact, the applicability of the entire clause itself is limited to CAS covered contracts. Consequently, the prospect for any withholding these days is drastically reduced as a result of the increased thresholds and unlikely application of the CAS to a particular contract. After all, the CAS apply to contracts and not to contractors.

Clearly, when the ACO decides to implement withholding contractors need to carefully scrutinize the list of contracts to which the withholding is to apply and ensure that they are CAS covered contracts. Remember that simply because a contract contains the CAS clause does not mean that the contract is actually CAS covered. There are numerous exemption to CAS coverage such as the trigger contract before CAS coverage can apply. Also, it is possible that a contractor's susceptibility to CAS coverage can ebb and flow with the existence of the trigger contract and the passage of accounting periods.

Corrective Action Plans

While the ACO's initial report did not ask for a corrective action plan the contractor may have already started working on making corrections either as a result of the initial report or perhaps even earlier as a result of the daily briefings with the review team. If so, the contractor's initial response as well as its final response to any deficiencies may already have identified any corrective actions taken or at least identify the corrective actions in progress and those that could be completed by the time the ACO is to issue his final report. If the contractor has implemented corrective actions or expected to complete corrective actions then the ACO can consider what is being done and confirm whether the contractor's system is still unacceptable.

In the event that the contractor is completely flat footed and has not taken sufficient corrective action until receipt of the final determination, the ACO will request the contractor to present a corrective action plan within 45 days.

Consequence of a Disapproved Business System

Other than the potential for withholdings the various business system clauses do not reveal any consequence for having a disapproved business system. So, the question becomes, "What is the consequence of having a disapproved business system?" Of course there are other questions, too, such as,

- Is having a disapproved business system anything that actually matters for the contractor?

- If it does not have any real consequence, other than the withholding aspect in the few situations when that can occur, is that perhaps prima facie evidence that any finding of a significant deficiency is not actually present?

As it turns out, it is quite possible that there are no significant consequences to the contractor but that is a very fact based determination.

SYSTEM |

CONSEQUENCE OF DISAPPROVED SYSTEM |

ACCOUNTING |

The Accounting System Review clause is required when the following contract types are contemplated (a) A cost-reimbursement, incentive type, time-and-materials, or labor-hour contract; or (b) A contract with progress payments made on the basis of costs incurred by the contractor or on a percentage or stage of completion. A disapproved system determination does not automatically disqualify a contractor from receiving additional awards for which an acceptable accounting system is required. In fact, the risks of a disapproved accounting system can be mitigated and awards still made if certain actions are taken like selecting a different contract type. (see DFARS 42.7502(g)) |

ESTIMATING |

While all DoD contractors are expected to have acceptable estimating systems, the Estimating System review is targeted toward contractor proposals for negotiated contracts involving cost or pricing data. Thus, a contractor's estimating system whether approved or not has no bearing on other kinds of contract awards such as competitive awards without cost or pricing data. For those negotiated awards involving cost or pricing data there are no expressed regulatory requirements expressed in the contract clauses or regulations for denying contractor awards in the event that the contractor does not have an approved estimating system. In addition, there is no expressed regulatory element of the source selection process that requires the contractor to have an approved estimating system. The prices for negotiated contracts are set by just that, negotiating. Also, supposedly the entire purpose for cost or pricing data is to put the government in the same position as the contractor when it comes to knowing the facts important to the negotiation. The fact that the contractor's estimating system does not produce the same number as the government's estimate is not relevant nor is it a contractor advantage that needs balancing nor a situation that needs to be avoided by withholding contract awards until the system is corrected and deemed "approved". About the only recourse is for the government to withhold a percentage of payments when the DFARS clause 52.242-7005 exists in the contract as discussed in the section above on withheld payments. |

MATERIAL MANAGEMENT (MMAS) |

Under DFARS 52.242-7004 there is no basis to withhold awards in the event of an unapproved contractor system. Rather, the contractor must correct the deficiencies and submit a corrective action plan but there is no provision within that DFARS clause for withholding contract awards until the corrective actions are implemented. About the only recourse is for the government to withhold a percentage of payments when the DFARS clause 52.242-7005 exists in the contract as discussed in the section above on withheld payments. |

PURCHASING (CPSR) |

According to FAR 42.201-1 if a contractor has an approved purchasing system the contractor only needs consent to subcontract for whatever subcontracts the contracting officer puts in the subcontracts clause of the contract. On the other hand, if a contractor does not have an approved purchasing system then the contractor needs the government's consent to subcontract whenever the contractor has a cost reimbursement contract, time and material contract, labor hour contract, unpriced letter contract and even for fixed priced contracts above the simplified acquisition threshold. Clearly, if none of those situations exist then a deficient purchasing system is not a basis for the government to withhold contract awards. It is quite possible that any contractors could avoid these situations in many of their contracts. In those few cases where there might be a problem then it is always possible for the contractor to receive consent to subcontract for a particular subcontract and be able to still get the award even with a deficient purchasing system. |

PROPERTY MANAGEMENT |

Under FAR 45.104(a) contractors are not responsible for government property under cost reimbursement contracts, time and material contracts, labor hour contracts and fixed priced contracts when cost or pricing data was provided. In all other cases, the contractor is responsible for any property provided to it by the government. Under FAR 45.104(b) the Contracting Officer can revoke the government's acceptance of risk when the contractor's property management system is not compliant with contract compliance. Consequently, an unapproved property management system is not a basis for the government to not make awards. Rather, an unapproved property system can simply result in the government revoking its assumption of risk in those cases where the government assumes the risk of loss for government provided property. This nuance is something that a contractor may have to explain to the government in the case where a contractor's property system has been determined to be unacceptable and the government claims that awards cannot be made to the contractor until the deficiencies are cured. |

EARNED VALUE (EVMS) |

Under the DFARS clause 52.234-7002 there is no basis for the government to withhold awards in the event of a significant deficiency or even a lack of an accepted EVMS. Rather, the options are simply for a review to be conducted within 180 days of award or the contractor to correct the deficiency or to submit a corrective action plan that fixes any system deficiency. Even the policy guidance instruction in the EVM Implementation Guide at 2.4.8 is a little sketchy. While it indicates that the contractor should provide a corrective action plan it only says that "contractual remedies may be appropriate" when adequate progress is not made correcting the deficiencies. |

While the business system reviews apply to both prime contractors as well as subcontractors meeting the threshold criteria, if the contractor is not a prime contractor then the government has no privity of contract with which to impose any restrictions on future awards or even impose other restrictions like withholdings. Nonetheless, the ACO may send letters to the subcontractor's customers and share the fact that its business system has significant deficiencies and has not been approved. This would then put the contractor's customers in the position of having to decide their course of action with the contractor and whether it should be given any new awards and is subject to any withholding. For a subcontractor this could be time for a critical analysis of the flow-down clauses and how the subcontractor's customer has tailored those clauses. If not tailored properly the subcontractor's customer may not have any contractual ability to impose any kind of adverse consequences on the subcontractor. At least with respect to the withholding provisions of a failed business system, there is no flow-down requirement for the DFARS clause 52.242-7005 whose presence is required in the contract for withholdings to be imposed.

Disputes

Contractors can well face situations where the procedures claimed as significant deficiencies by the government result in the contractor having to incorporate the government's mandated fixes at considerable cost consequences to the contractor. In fact, contractors could find that adopting the government's proposed procedures are anathema for both cultural and practical business reasons. Nonetheless, the contractor could find it very difficult to simply resist the government's system disapproved moniker and withholding penalties and instead be forced to comply at great cost to the contractor.

In such cases all is not lost, however. If the government is wrong in its assessment of a significant deficiency and its insistence that the contractor make a change to an otherwise compliant business system then this is also a change to whatever contracts are effected by such a change. In such a case, the contractor does have a means to make a claim against the government for the increased costs that it will incur as a result of having to implement the government's mandated change to an otherwise compliant contractor business system. While few in number, this kind of changed condition to contract requirements have been found in the past and the entire cost of government's mandated changes passed onto the government by way of a contract price adjustment. The process that the contractor would follow is the same as any other disputed item that would start as a Request for Equitable Adjustment (REA). (see the discussion of Managing Requests for Equitable Adjustment for Constructive Changes in Federal Government Contracts)

As explained in this article on Managing REA's and as stated above, the decision maker in these reviews is the ACO and not the review team. At the same time, there are numerous stakeholders involved to whom the ACO must obtain concurrence, and as explained in the article on Managing REAs contractors need to understand the role played by each of the stakeholders and determine what kind of support needs to be provided to the ACO not just to obtain his concurrence but to equip the ACO with the support necessary to overcome any objections from the other stakeholders to whom the ACO must get concurrence.

Of course, it is better to avoid going the disputes route. In fact, it is better to use the process discussed below on Responding to Findings to manage any adverse findings. Nonetheless, sometimes there simply is no other remaining recourse than the dispute route. Contractors should know it exists and they should be very cognizant of the effect that any mandated fixes could have on their business, particularly when their business systems already were compliant with regulatory requirements.

Contractor Strategies for Managing a Contractor Business System Review

In certain situations, contractor business system reviews are inevitable even for small businesses. For example, if a contractor will be receiving government property it must have an approved property system regardless of their size. Otherwise, the contractor will not get the award for a contract where government property is an essential part of the deal. The same can be said of an earned value system review.

Self Assessment

Contractor will likely know well in advance that a business system review is coming. This is true for several reasons. First, there will probably be rumblings from the government that the contractor is being evaluated for whether a business system review is warranted well before one actually occurs. Sometimes those rumblings start even before the contractor actually trips the threshold criteria. The government may or may not have the real details about a contractor's business and status particularly when it is a subcontractor. Of course, the contractor may be aware of its status and whether it trips the thresholds for a business system review well before the government ever figures it out. In those cases, it makes good sense for the contractor to go ahead and initiate some kind of self assessment of its status as a candidate and as a compliance risk.

Self assessment as a candidate

It is always a good idea for contractors to know whether they actually meet the requirements of a business system review. If a contractor determines that it is a candidate then it can move to the next level and conduct a self assessment of its compliance with the business system criteria. If the contractor determines that it is not a candidate that can be good information to have ready to share with the government when the first rumblings from the government of a business system review start to occur. Of course, that does not always mean the government will accept the contractor's representation but it can be good information to share and provide to the government reviewers when they start their review so that they can quickly confirm that the contractor's representations are true and decide to by-pass the review after all.

Self assessment as to compliance issues

Whether or not a contractor meets the thresholds for a business system review a self assessment as to the contractor's compliance with the system requirements is a good idea. Certainly, if the contractor is a candidate for a business system review then a self assessment should be performed in order to get ahead of things and know where any problems exist.

Pre-Emptive Corrective Actions

If the self assessment identifies compliance issues then go ahead and devise a corrective action plan and get it going. Even if the review team finds problems, if the corrective action is already in place then system disapproval can be avoided as well as any potential withholdings.

Monitoring the Review

Monitoring the review is always an important tactic for surviving any business system review as well as any kind of audit in general. When well monitored there will not be any surprises at the exit conference. In addition, real-time monitoring of the review team progress provides the contractor an opportunity to either initiate corrective action planning or advise the review team management of any assessment errors or misunderstandings that they have made. A system review is a big undertaking for government and contractor alike. It is quite possible that the review team could be operating with incomplete or erroneous understandings of the contractor's business and operations. It is always better to get any misunderstandings corrected prior to them becoming the basis for an interim finding. Correcting a wrong trajectory just gets tougher as the process moves forward.

Responding to findings

Throughout the business system review process contractors should have many opportunities learn of potential and/or actual findings and respond to them. Moreover, prior to publication of any formal findings by the government, both contractor and government should encourage having open dialogue and information exchange. The objective should be to obtain a contractor business system that functions as required and produces reliable information. The business system review is not intended to be an exercise in developing findings.

Nonetheless, the review could result in findings either as to anomalies in system operation or even as more serious "significant deficiencies". As explained above, a determination of "significant deficiencies" and the potential or actual determination of a disapproved system will occur at two places. The first is the initial determination and the other is the final determination and they can be as much as 60 to 90 days apart. Consequently, contractors can have significant time in which to proactively manage their destiny.